[Views are my own and not those of the Yale School of Medicine.]

As a developmental psychologist, it’s tough for me to watch shows about children and teens. All too often, popular shows propagate inaccurate, negative stereotypes and spread misinformation that steers kids and their caring adults in the wrong direction. But given the popularity of the miniseries Adolescence and the discussion it’s generating, I steeled myself to watch it. I wanted to know: Is it really about adolescence, and is it helpful or harmful to watch?

The four-episode miniseries follows the harrowing investigation of Jamie, a thirteen-year-old accused of murdering his schoolmate Katie. The question of whether he’s guilty is settled early via incriminating CCTV footage. The remainder of the show focuses on the question of who or what may have caused this nightmare, and the writers interrogate the possibilities one by one. The show touches on themes of cyberbullying, social media, and toxic online culture; the pain of humiliation and rejection; intergenerational trauma; and the fragility of teen identity.

First, I’ll share my opinion: I wish the series hadn’t been made. It exploits parents’ worst fears—that the world will damage their child; that they’ll be unable to stop something tragic from happening; or that they’ll be in the dark, the last to know about dangers stalking their child—all while failing to provide solutions for the problems teens actually are facing. Today’s parents (at least in the United States) are already buying bulletproof backpacks to protect their kindergartners from school shooters and limiting their teens’ social media use to protect their mental health—in addition to monitoring age-old risks like substance use and unsafe sex. All of this adds up to an overwhelming burden of anxiety and responsibility that should not be left solely to parents. So the series feels like a cheap shot, a gratuitous grab at the low-hanging fruit of parents’ anxiety. Any profession that takes the raising of kids seriously is ethically required to care for families if they upset them, but media gets a pass—for the sake of entertainment—while profiting from it.

Does the miniseries get teens right?

The title Adolescence is admittedly attention-grabbing. It is a broad heading that implies that the series will inform viewers about this age group and (given the ensuing plot) that it will draw a connection between this period of development and the potential for murder. However, Adolescence is a work of dramatic fiction, a piece of art intentionally constructed to provoke, to shock and appall, to stir feelings and raise alarm in order to attract viewers and get people to talk about the show. However, it should not be mistaken for an accurate education about the period of adolescence (on which I’ve taught many courses at the university level). And, importantly, while it raises questions about this period, it does not point to the solutions that we know exist.

That said, it does have some echoes of some qualities of teens that are unique to their age. Kids 10 to 14 are going through the onset of puberty, including hormonal changes that remodel the brain to prepare them for adulthood. Evolution has engineered teens’ brains to motivate them to eventually leave the nest, form communities, mate, and assume the responsibility for adapting society anew to changing environments. In the early stages, these initial brain changes are abrupt and pervasive. They alter teens’ thinking, emotions, decision-making, and behavior. Young teens become more sensitive to others, more attracted to novelty and risk, and more experimental in their search for identity and belonging than any other age group.

In Adolescence, some of these dynamics are on display:

The need for social acceptance is a driving force in early adolescence. It’s a time when teens sort their identity from those of their parents. But young teens aren’t yet sure who they are, so they look to their peers for a temporary identity. This can be fraught, since their peers are also in flux, and few have developed good coping skills—after all, it’s everyone’s first rodeo.

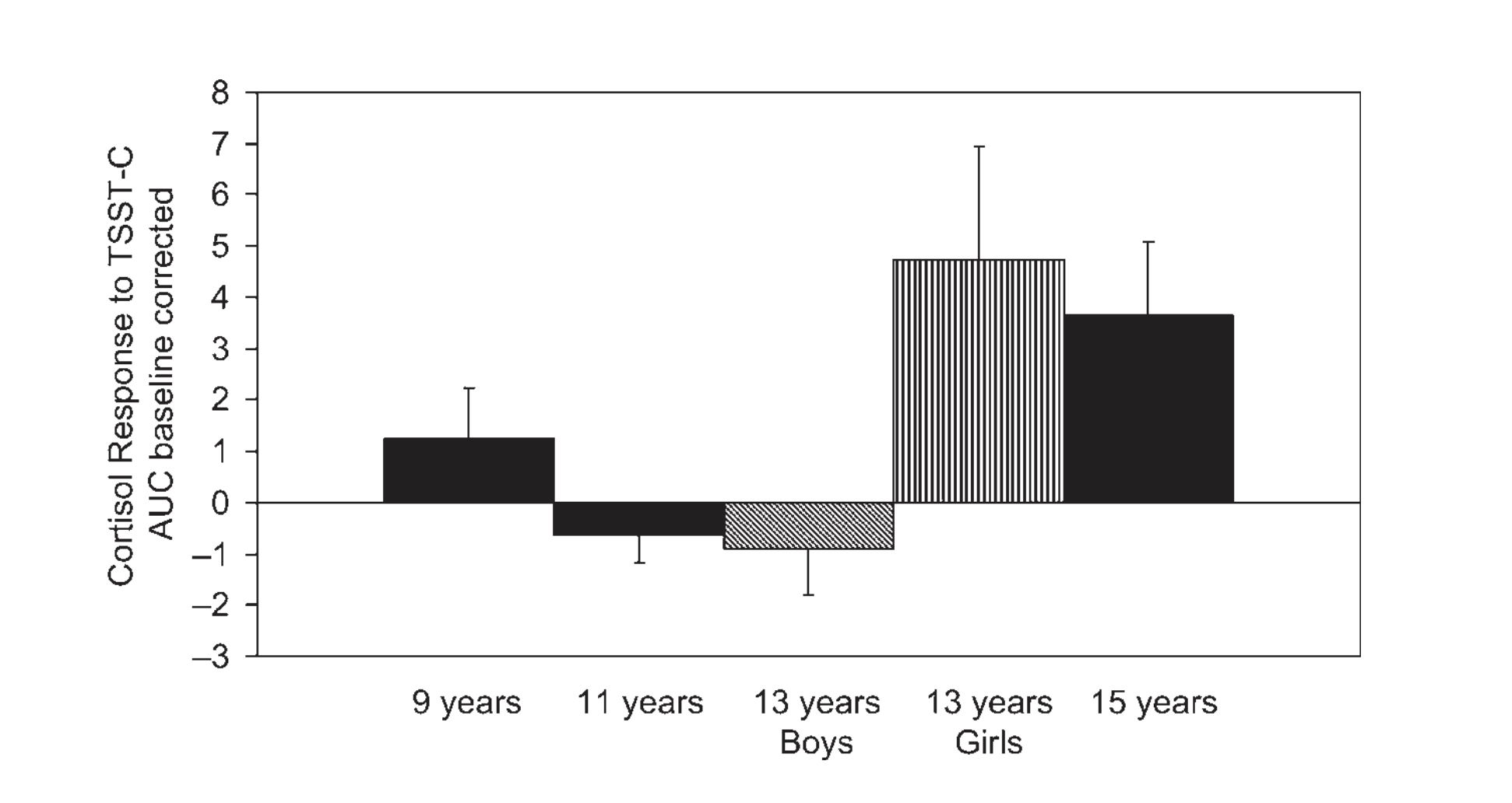

Research reveals the biology of just how high-stakes peer acceptance can feel. For example, when young teens are asked in studies to give a speech while they think their peers are observing them, their cortisol spikes above the levels experienced by younger children who perform the same task. This, along with other studies, suggest that from 11 to 14 or 15 years of age, kids are more stressed in front of peers than people at any other age.

Cortisol response in children and teens to giving a speech in front of peers. From Gunnar, M.R. et al., 2009

The need for acceptance and the pain of exclusion course through Adolescence. In a virtuoso display of acting, the young man playing Jamie (Owen Cooper) demonstrates how deeply the character’s ostracism has cut, exposing excruciating shame and agony. To the counselor who is assigned to evaluate him, he shrieks, “Do you like me? Don’t you even like me a little bit? What did you think about me?”

In young teens, the desperate longing for approval lives side by side with a growing need for a psychological separateness, for independent thought and decision-making. Many parents will have heard versions of Jamie’s plea for respect when he snaps at the counselor, shouting, “You do not control me!” and “You do not tell me when to sit down!” It’s a reminder that threats to a young teen’s emerging autonomy are a third rail, a line to be approached with great care.

Some of the brain changes in teens create faulty thinking. They don’t yet have the mature judgment of adults, though we often make the mistake of thinking that they should, given their physical size. Studies show that around 14 years of age, there is a brief period of degradation in their gradual ability to plan ahead, make wise decisions (especially in the presence of peers), and manage their impulses. Young teens are famously “all gas and no brakes,” since their hastiness frequently overwhelms their ability to check themselves.

In the show, the counselor interrogates the maturity of Jamie’s judgment: Does he understand the permanence of death, the consequences of his actions, or the sexual activity that’s appropriate for his age? (Yes, yes, and no.) In the U.S. this evaluation would bear on his sentencing. Developmental expert Lawrence Steinberg argued in an amicus brief to the Supreme Court that teens are less culpable for their crimes due to their developmental immaturity, susceptibility to peer influence, and greater potential for change. This led to the abolishment of the death penalty and life without parole for juveniles.

Given these elements of adolescent brain development, does it follow that Jamie’s adolescence alone is responsible for the havoc he wreaks? In a word, no. In 2021, less than 1% of teens (0.5%) aged 12-17 years old committed a violent crime.¹ Viewed another way, in 2020 only 7% of total violent crimes were committed by youth under age 18 compared to 93% committed by adults, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. If the title of the show is meant to imply that just being an adolescent raises one’s risk for murder, that’s inaccurate. There’s a pretty infinitesimal chance that just being an adolescent raises one’s risk for murder.

Implying that teens are inherently troublesome, volatile, or violent wrongly reinforces an old, biased and destructive stereotype of adolescence as a period of “storm and stress.” Instead, current science views adolescence in the opposite light, as a period of positive growth and tremendous potential—for creativity, idealism, social good, and sensitive care. They are biologically designed to envision and lead society toward a better future; it’s not a coincidence that most social justice movements have been led by young people.

But how an individual’s adolescence plays out depends on the quality of the environment in which they’re growing. During puberty, the brain over-produces synaptic connections because it’s awaiting input from the environment about which connections are important. It then prunes back the unnecessary ones. You may have heard the adage “The neurons that fire together, wire together.” (The ones that don’t fire are eliminated.) Nascent research shows that the stress regulation system is also remodeled during this time, and it, too, recalibrates according to the level of stress teens are experiencing around them. In other words, a young teen’s brain and body are extra-sensitive to their environment, and how it feels to them will literally become embedded in their body and brain.

Multiple suspects: wider social forces.

Given this extra sensitivity to their environment, unhealthy and unsupportive surroundings can deliver an extra whammy to teens.

For 50 years, science has shown that development is a seamless and continuous interaction between nature and nurture. Who a person is at any point in time is a result of how their unique biology as an individual interacts with the layers of social environments surrounding them—environments that include their home, school, neighborhood, country, and economy. The more distant forces, including culture and social norms, are transmitted through direct one-to-one relationships, and it’s caregivers, siblings, peers, and teachers—whether virtual or in person—who have the most power to influence a child.

Here’s how the prominent developmental theorist Urie Bronfenbrenner diagrammed the child nested within multiple layers of contexts:

In this view, development at any point in time is “co-constructed,” or the result of multiple forces interacting simultaneously across any of the layers. These influences are also filtered through the characteristics of the child, who can be an active agent in their own development. For example, two children of the same parents—Jamie and his sister in the show, for example—may turn out very different due partly to differences in their temperaments, genetic inheritance, abilities, and more.

In his groundbreaking 1979 book The Ecology of Human Development, Bronfenbrenner writes that parents’ power to affect their children is paramount—but it’s also limited by the environments and time periods in which they live. How children fare, he explains, depends on how well society’s goals are aligned with their wellbeing. Unfortunately, in the United States (and to some extent in the UK, at least as portrayed in Adolescence), societal forces are currently badly misaligned with healthy child development. The social contract where communities collectively support its members has broken.

Adolescence reviews some of these wider societal forces. For example, has a restrictive view of masculinity played a role in making Jamie capable of murder? In an attempt to “toughen him up,” Jamie’s working-class father, Eddie, pushed his son toward sports instead of fostering his real interests in art and history. The series raises the question of whether that choice backfired, instead brewing a storm of anger or resentment within Jamie.

Jamie posts pictures of models on his social media in an effort to boost an image of what he thinks his masculinity should be—that of a “player,” a young man attracted to (and presumably desired by) beautiful women. But Jamie and a peer are taunted by their classmates for their immaturity and called “incels,” a term meaning “involuntarily celibate.” Even when Jamie makes a genuinely kind overture to Katie after she herself is cyberbullied, (a topless photo of her circulates on social media), Katie reacts viciously, publicly rejecting him, and the show flirts with the suggestion that her behavior could have brought on Jamie’s retaliation.² The “manosphere” (the deeply misogynistic strain of culture found in blogs, websites, and podcasts) is increasingly reaching young men through social media and algorithms, encouraging them to blame women and see themselves as victims of sexism. (For more analysis of masculinity and the miniseries, I recommend the social psychologist Brendan Kwiatkowski’s blog post about the show at remasculine.com/blog.)

Next, the investigative gaze shifts to the internet and social media. Jamie’s mother Manda laments to her husband that they weren’t able to protect Jamie despite the fact that he was under their roof. “He was in his room, wasn’t he?” she says. “We thought he was safe, didn’t we? What harm could he do in there?” She’s had no awareness of the harassment stalking her son from beyond their walls.

Unfortunately, in the current state of technology, parents have to find a way to gain that awareness. While in-person interactions begin and end by entering or exiting a door, virtual relationships aren’t constrained by time and place. Users can participate in many interactions simultaneously, be in multiple spaces simultaneously, or engage asynchronistically. When children are in their rooms, parents should never assume that they’re alone if they have a device that’s connected to the internet.

Now, current guidance suggests that parents should restrict young teens’ screen use overall and especially restrict their access to social media until ages 15 or 16. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, in his book, The Anxious Generation, makes a strong developmental case for postponing kids’ access to social media as long as possible. Instead, kids can have “dumb phones” that allow only texting, calling, and emailing. Adolescent expert Lisa Damour recommends that when access is finally allowed, parents should scaffold their kids’ use by systematically educating and supervising them. “Dance like no one’s watching,” she says, “but email like you’ll be subpoenaed.” Everything that transpires online will eventually be available to a potential employer, she adds.

Until media and technology decide to be supportive of young people’s development, it falls to parents to buffer their children from those harmful forces.

What does the show miss?

Completely absent from consideration in Adolescence is the role of the school. How has such intense bullying gone unnoticed by an adult with the power—and responsibility—to intervene? The show depicts eruptions of bullying on school grounds, and several teachers are aware of brewing trouble, yet none of them does a thing.

In 2023, about one in five young people 12-18 years old reported being bullied. Given teens’ social vulnerability, it’s no surprise that, in the absence of an intentionally positive context, bullying peaks in middle school: 25% of middle schoolers report being bullied, compared to 15% of high school students. Bullying is harmful for everyone involved—the bully, the target, the witnesses, and the school as a whole. Both the children who bully and those who are bullied have an increased risk of mental health problems that can follow them into adulthood and undermine their functioning, including an elevated risk of violence for both parties that can persist into adulthood. So while adolescence alone does not raise a risk for violence, being bullied does. The U.S. Secret Service determined that the majority of school shooters had been bullied. Depending on the severity, bullying can be considered a form of abuse, trauma, and/or an adverse childhood experience.

Parents worry about bullying and their teens’ mental health. So it’s important for them to know that schools have a legal and ethical responsibility to keep all students safe, including safe from bullying. In the U.S., every state has legislation that prohibits bullying and requires schools to establish policies to prevent it. Though there is some variation by state, most schools are accountable even if the bullying happens off campus or on social media, and certainly if it spills over into school time. The United Kingdom, where the show is set, has a similar network of laws and policies.

What actually works in schools? Research shows that most “anti-bullying” programs that rely simply on raising awareness and enforcing consequences don’t work. What does work is when schools create a positive school climate and teach emotion and relationship skills—this leads to lower rates of bullying and violence overall. Students and adults alike report warmer and closer connections, and the students have higher achievement scores. Positive relationships with teachers are protective against peer victimization. When a school community is emotionally skilled, teachers can often quickly sense when someone is hurting, and they compassionately and effectively follow up. And teens, for their part, have more language and strategies for their feelings and conflicts.

Recommendations:

Both human rights organizations and developmental science recognize that young people are a vulnerable population in need of special protections simply because of how development works. But this social contract between families and the wider world appears to be broken. Numerous studies rank the U.S. lowest among developed nations in helping parents to support children. On almost any policy dimension, other countries do better on issues like affordable childcare, work-family policies, income parity, health, technology, or education. Recently, I attended an international summit evaluating social media and happened to be seated next to a European colleague. When I grumbled, “Why can’t tech companies police themselves in the interest of children?” he responded. “In Europe, we regulate problems. You Americans have to educate your way out of problems.”

Still, voices are rising in favor of regulations. Social psychologist Haidt calls for stringent restrictions on technology. Former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy is outspoken about the risks of social media, comparing “Big Tech” to “Big Tobacco” for the way companies obscure their own evidence for harm while maximizing kids’ engagement at the expense of their health and wellbeing. He calls for Congress to require warning labels on social media platforms, similar to warnings on tobacco. As a developmental psychologist, I would like to see developmental impact evaluations (much like environmental impact reports) from companies making products that touch aspects of children’s lives, directly or indirectly.

What can schools do?

Many schools are considering screening Adolescence for their students and/or parents. As I’m sure is obvious from everything I’ve just expressed, I strongly recommend against that—for multiple reasons. The show is a work of fiction that, while offering some important insight into adolescence in 2025, creates an extreme and unlikely case. Again, it is designed to provoke, and should not be viewed as a documentary nor presented as an education.

Schools should not raise parents’ fear and alarm more than they can mitigate them, and they certainly should not endorse the show’s view that there are no answers—especially if they are eschewing their own accountability. They should not perpetuate a wrong stereotype of teenagers as inherently volatile rather than accurately describing their incredible potential for good and how we can support it. In addition, many students could be traumatized by the show, especially the large number of students who already experience bullying as well as sensitive or empathic students who feel experiences more deeply. And finally, fear-based, “scared straight” tactics rarely work with teens. When they experience pressure coming from authority figures, their autonomy threat is activated, they feel manipulated, and the tactic often backfires, making teens more likely, not less, to act out.

What can concerned schools do instead?

Review and recommit to preventing bullying with evidence-based approaches. The Cyberbullying Research Center is one of the best resources from which to draw clear-headed guidance and inspiration. The RULER Approach, with which I’m affiliated, reduces bullying by teaching skills of emotional intelligence.

Offer parent education talks and/or workshops on the school’s approach to preventing bullying as well as on accurate teen development, supporting teen friendships, and dealing with social media.

Develop a charter for how your school and each classroom will foster the values and the actions that promote kindness, safety, and calm and connected relationships.

Cultivate—and measure—a positive school climate. Regularly collect data on how safe students feel.

Fully embed an emotion skills education into the curriculum. Teach skills directly, but even more importantly, model them every day throughout school life.

What can parents do?

I’ve written and spoken extensively about how parents and schools can prevent bullying. Recent research, however, has added some new insights. Studies show that a good relationship between parents and children beginning early in development helps to prevent trouble later on. When kids feel they can really communicate with their parents, it’s protective. Peer victimization is less likely to occur in the first place, and if it does happen, the harmful effects on the child are less intense.³ In general, in middle school, kids tend to talk less with their parents than they did when they were younger, and it’s hard to suddenly develop good communication once victimization begins. So maintaining a good relationship with trust, respect, and open communication all along helps to keep kids in a safe lane.

In addition, the following are helpful:

Normalize healthy conversations about relationships, e.g., how kids feel when they’re in a good relationship versus how they feel when it’s not good, and how to problem-solve interpersonal difficulties. Share some of your own relationship solutions (in age-appropriate ways). Verbalize values around relationships. Discuss relationship dimensions that appear in books, the news, or their surrounding world.

Studies show that conversations that are open, warm, somewhat structured, and—importantly—respect teens’ growing autonomy, foster resilience even amid difficulty. Conversations that allow for teens’ feelings, that encourage teens’ own problem-solving and self-reflection, and that are not controlling or directive are especially helpful.⁴

If bullying continues, communicate with the relevant educators, and go up the administrative chain as necessary until the problem is resolved.

Document interactions with the school through follow-up emails, constructively and kindly confirming what was discussed and agreed upon.

If cyberbullying occurs, take screenshots, and report activity to the platform. (Find more guidance at cyberbullying.org.)

We live in a network of embedded systems, and parents can’t possibly make up for the failures of society to protect their kids. All kids are sensitive, and young teens are especially vulnerable to the toxicity all too readily accessible on the internet/social media, as well as to the bullying that goes unchecked there. We didn’t need a show like Adolescence, but perhaps we can use it wisely to deepen our commitment to supporting teens—and all our children.

In 2021, about 123,000 serious violent crimes were committed by youths aged 12-17 years old. There are roughly 25 million in this age group, so that works out to about 0.5%. https://www.statista.com/statistics/477466/number-of-serious-violent-crimes-by-youth-in-the-us/

A note about Katie’s point of view: We never get it, and that’s part of the point of the show. This is a series that intentionally interrogates the experience and motivations of the perpetrator and not the victim.

Slade, S. G. (May, 2025). Peer victimization, self-blame, and rumination during middle childhood: The protective role of parent-child communication. Presented to The Society for Research in Child Development, Minneapolis, MN.

Kim, S.G. (May, 2025). Peer victimization and youth internalizing symptoms: The role of observed maternal behaviors. Presented to The Society for Research in Child Development, Minneapolis, MN.