I recently attended a baby shower where guests were asked to write advice on a card for the parents-to-be.

Get help, I scribbled. Lots of help. Any kind of help—with cooking, cleaning, errands, venting, sharing—anything to free you physically and emotionally so you can fall in love with your baby and become a family. Oh, and stay in your pajamas for a month—it lowers others’ expectations of you.

Before I had children, I read With A Daughter’s Eye, Mary Catherine Bateson’s memoir about growing up with famous anthropologist parents, Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. Mead, the “Grandmother of Anthropology,” was a pioneer in the study of family life in worldwide cultures, and she used her understanding of varied family patterns to shape her own.

“Nobody has ever before asked the nuclear family to live all by itself in a box the way we do. With no relatives, no support, we’ve put it in an impossible situation.”

“She set out to create a community for me to grow up in,” Bateson writes.[1] “I did not grow up in a nuclear family or as an only child, but as a member of a flexible and welcoming extended family, full of children of all ages, in which five or six pairs of hands could be mobilized to shell peas or dry dishes.”

Mead thought it was preferable for children to be raised in a network of caring people, to be part of several households with several caretakers, as she had observed in her studies in Bali, New Guinea, and Samoa. She considered a nuclear family too tight a bond, too likely to “create a neurosis.”[2] Instead, she advocated for “cluster” units comprised of older married couples, singles, and teenagers from other households. This also freed Mead to work and travel away from home more.

“My mother’s arrangements…had the…quality of that kind of lacework that begins with a woven fabric from which threads are drawn and gathered, over which an embroidery is then laid, still without losing the integrity of the original weave,” Bateson writes.[3]

How did it feel to Bateson to have multiple caregivers as a child? Memories of her childhood are cast in a “rosy light,” she states. It was a “utopia,” and she considered herself “rich beyond other children.” She adds that she’d have to “dredge deep” to come up with an unhappy memory about the arrangement.

This idea planted a seed in me. When my husband and I decided to have children, we were thousands of miles away from our families. The thought that we could cultivate a viable family structure from other kinds of relationships was inspiring and liberating. It changed my life and the fabric of our entire family.

Around that time, a friend entered our lives. Like me, Elnora is a white American, but she had spent years in India as an exchange student. In fact, she’d attended college there, spoke Hindi, and had lived with my husband’s extended family. As a result, she understood both his culture and mine. She’d known my husband since he was ten, and I came to know her when she moved near us in the Bay Area for a position in hospital administration.

I didn’t set out to make her make her a part of our family; instead, the relationship grew organically. I was attracted to her maturity, her psychological centeredness, and her kindness. When the birth of our first baby approached, I asked her if she would accompany us to take photographs—I trusted her more than anyone for this vulnerable moment. Afterwards, she and the baby bonded, and she began to visit us weekly to watch her grow. I noticed that we felt lighter when Elnora was around and were better versions of ourselves in her presence.

“I knew from the beginning I didn’t want to have children,” she told me later. “I didn’t always have a good experience as a child, and I didn’t want the responsibility of raising my own. But I had a deep wish to be connected to a family—and then you showed up!”

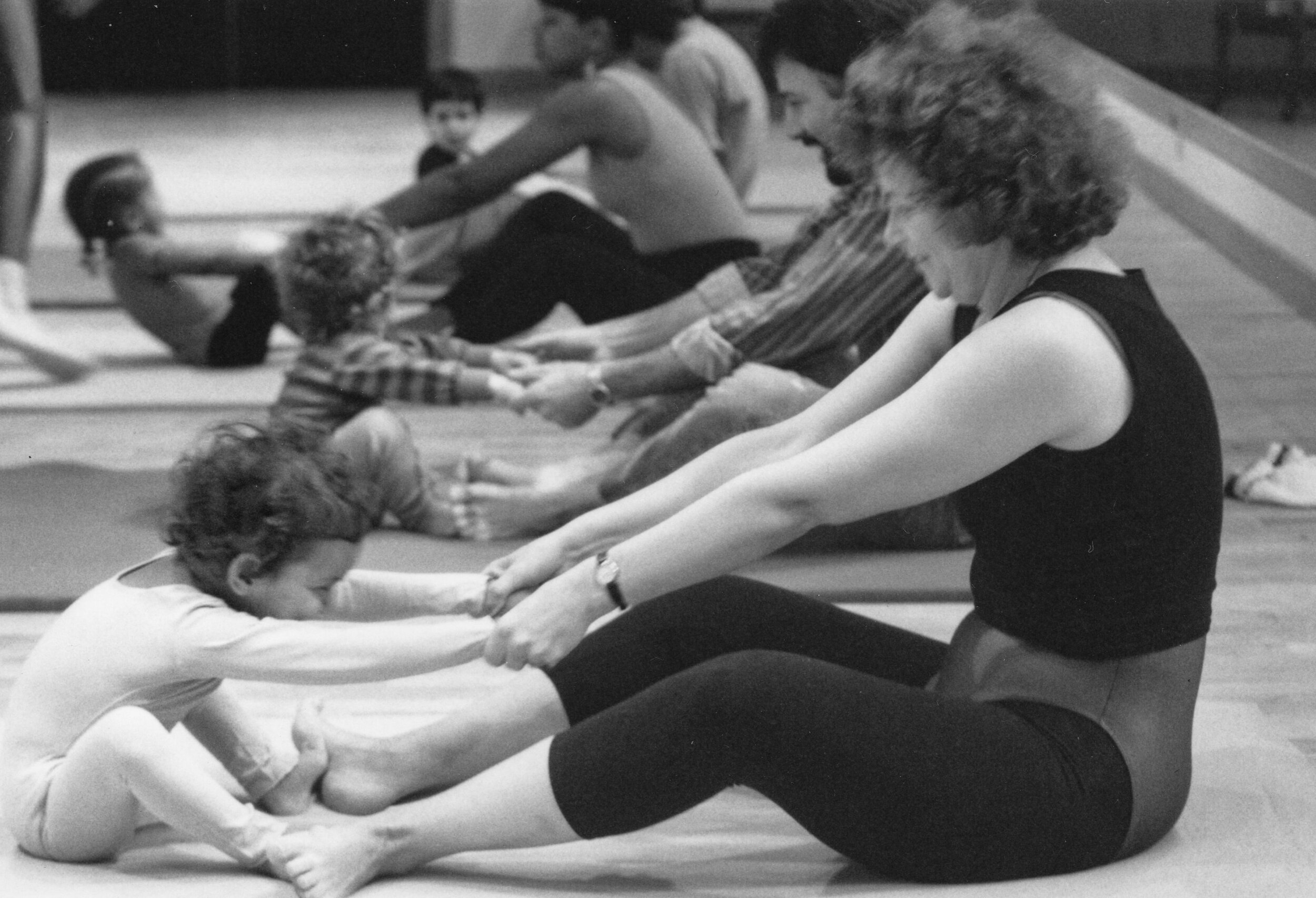

Later, she helped me birth our second baby. When it came time to push, I sat across Elnora’s and my husband’s thighs, my arms around their necks. She wiped my forehead and massaged my shoulders. She was the first person to hold the baby after my husband and myself.

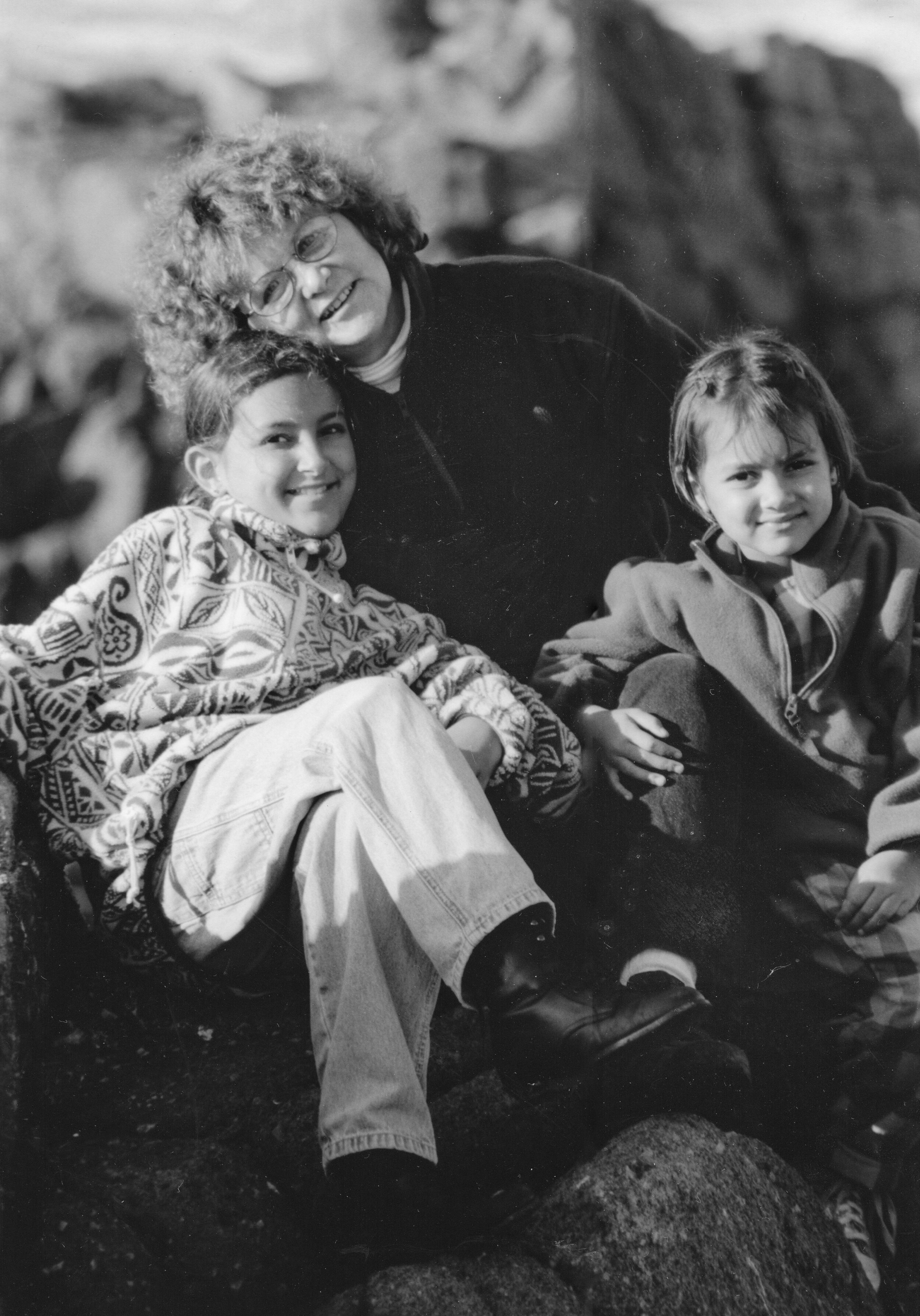

Our closeness grew over the years. She babysat, brought us food when we were sick, and celebrated all the holidays with us. She was our person. In turn, she embraced the open, disarming love of children, and discovered that she was, in fact, good at such relationships. The children had their first sleepovers at her house (she even kept children’s Tylenol in her cabinet for midnight leg pains), and she was the “homework fairy” who made studying fun without fomenting rebellion. We invited her to travel with us, and she did, frequently—eventually attending college graduations, weddings, and even my mother-in-law’s cremation in Bombay. To us, she was “Lala,” “godmother,” or “fairy godmother,” but anthropologists would call her an “alloparent”—a non-parent who provides parental care to the young.

Over the years, we continued to cultivate a relatively open household, and we were fortunate to engage with different kinds of alloparents. Many young people lived with us on their journey to adulthood, especially those from the Indian side, where joint families are typical. One young man, a physics major at the local university, performed science demonstrations for my children and their friends. A beloved babysitter was so integral to my ability to work, I told my mother-in-law that she had to obey the sitter in order to stay with us—certainly a violation of her expected social order. Other alloparents emerged, too—a tutor, a favorite teacher, even some of the college students I taught. Other parents were also great allies. In the summertime, our children flowed through the homes of other families, and we parents shared everything from information on sleepaway camps to our positive observations of each other’s children. We were designated family guardians in case of death, and later, I even officiated at the wedding of one of my daughter’s childhood friends.

A network of caring people engenders security in children. For my own kids, there was no doubt about a sense of belonging when their entire “posse” (their word) showed up for school performances and graduations. Having multiple caring adults around also made it easier for me to have a bad day: I could withdraw, knowing that some other buoyant spirit would pick up the slack. It also brought more diverse perspectives and temperaments into the mix. My children got to witness as my niece started a business and became a persuasive public speaker, in the process offering a model of what an energetic extrovert could do. And when a young teen starts to individuate, it’s helpful to have another eye on things while not threatening their autonomy.

What does the research say?

We are not meant to go it alone. In anthropology, humans are considered “cooperative breeders,” and researchers routinely document the contributions of alloparents along with biologically related ones. Learning this was a great relief to me, a refreshing departure from the conventional American view that mothers alone must bear the burden of care—an arrangement which the pandemic has proven particularly fragile and unsustainable.

Research on almost any topic in developmental science shows that social support to the family improves developmental outcomes. For example, one of the strongest predictors of resilience in the face of trauma is the presence of any supportive adult for a child—an aunt or uncle, teacher, coach, or friend. Postpartum depression occurs less often when women are surrounded by helpful people after birth. Children’s talents are more likely to develop when a non-parent adult takes a deep interest in them. And teens navigate the bridge to adulthood more successfully with the help of older mentors.

Grandmothers are a well-studied type of alloparent, and the “grandmother hypothesis” ascribes them a critical role in supporting human evolution. Across history, the presence of a grandmother is associated with improved child survival rates and greater numbers of children. For millennia, grandmothers have foraged, cared for the young while parents worked, passed on parenting, cultural, and economic information, or assumed complete care when a parent was not available. They have also provided emotional support when children struggled with a parent or the arrival of a new sibling. In one study, a grandmother’s presence was shown to reduce the child’s cortisol (a stress hormone) during stressful family dynamics.

The hard parts

However, things don’t always go swimmingly.

The support that is offered must meet the support that’s desired, writes noted developmental scientist Urie Bronfenbrenner in his book The Ecology of Human Development. One of Bronfenbrenner’s missions was to prove that support of all kinds—close-up or distant—significantly affects children’s development. But he pointed out that not all support is intrinsically useful. What matters most is how the help is felt by the recipient.

In my own experience, I found that thoughtful communication, clear boundaries, and a healthy dose of forgiveness were key. Periodic conversations about how things were going were useful, too. I sometimes served as an intermediary between the children and an alloparent, facilitating their alliance. I frequently explained the child’s developmental status, shared ideas for birthday gifts, or oriented our chosen family member about a child’s current struggles. In turn, I sometimes coached the children about how to interact with someone’s unfamiliar style of relating. And I taught them that acknowledgement and reciprocity mattered—thank you notes, a bowl of soup in the midst of a flu, help with chores, or, as they grew, a new music playlist and help with technology were offered in return.

Once in a while, I had to provide corrective guidance, or—more rarely—let an alloparent go if I thought they were not a positive influence on the kids or our family as a whole.

“I was mortified that I was sharp with the girls, once,” Elnora admitted. “You have to have an artful ability to take feedback if you’re going to be intimately involved with another family.” To her great credit, she was flexible with our last-minute schedule changes and requests and patient with our child-centered focus and family distractions. I’m sure she didn’t always get the attention she deserved. Family life can be messy.

Then, too, some parents might feel jealous of other people’s close relationships with their children, or they might wonder if another relationship will undermine their child’s formation of a secure attachment. But to children, there’s no question about who their primary attachment figures are, as long as those caregivers are involved with, and attuned to, them. Children are biologically organized to form a “small hierarchy of attachments,” and under normal circumstances, parents are situated at the top. Other attachment figures can offer comfort and developmental scaffolding, but they are backups to the primary attachment. In my case, I believed my children were safer in a larger network, and I was grateful for others’ loving, constructive relationships with them.

What’s in it for alloparents?

“What did you get out of caring for a child who is not your own?” I recently asked Elnora.

“My connection to your family was life-changing—life-affirming,” she told me. “My childhood had rough spots, and I knew I didn’t want to have children myself,” she said. “You needed help, and I needed a family. With your kids, I was happy to learn that I could have meaningful relationships with children.

“And I got to play again! I got to ride merry-go-rounds and tiny trains, do craft projects, and I found I was not bad at storytelling or planning parties.

“I learned about child development and issues like discipline and cooperation that even spilled over into my job. I became a softer supervisor at work, more interested in my employees as whole persons.

“And I received the love and affection of children, going on 33 years now.”

The freedom to choose

In human evolution, families are designed to keep adapting to changing circumstances, and we can see that families in the U.S. are under a slow but steady process of remodeling. As of 2014, the heterosexual nuclear family in which parents stay married is no longer the dominant family form. Instead, over the last 60 years, there has been an increase in cohabitating caregivers, second marriages, blended families, and single caregiver households. Many children live with grandparents, either exclusively or along with a parent, and a small but increasing percentage (292,000 children) live with same-sex parents. Queer families have long been on the vanguard of creating “chosen families,” often out of necessity, and now the phrase is increasingly common in Millennial parlance. Research shows that it’s not the family form that matters to children’s development as much as how the relationships feel.

“We all must compose our lives without relying on single role models,” Bateson writes.[4] One can look to other kinds of families for inspiration, she says, but above all, her mother’s work affirmed “the possibility of choosing.”

This Mother’s Day, one of my daughters wrote to Elnora, “I feel so lucky to have multiple adults in my life who looked out for me, guided me throughout the world, and continue to be here for me.” My other daughter, echoed the same sentiment: “I’m so lucky to have two amazing mother figures in my life to love and support us along the way. My own future family will be so lucky to have all these people who love them already!”

Elnora replied, “It’s been a special, extraordinary experience to be this close to you for all of your lives.”

And every year I write to her, “I couldn’t have done it without you.”

[1] Bateson, M. C. (1984). With a Daughter’s Eye: A Memoir of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. Harper Perennial, p. 7.

[2] There is no research, to my knowledge, that verifies this statement.

[3] Bateson, M. C. (1984). With a Daughter’s Eye: A Memoir of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. Harper Perennial, p. 22.

[4] Bateson, M. C. (1984). With a Daughter’s Eye: A Memoir of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson. Harper Perennial, p. xvii