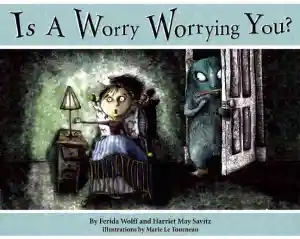

When I was young, I worried so much that my parents called me Worrywart and bought me a stuffed toy with the same name. It wasn’t the best strategy—I was left feeling bewildered and wondering how to not worry—but what did parents know then? Research from the field of developmental emotion science finds that children who understand and manage their feelings are happier, have better relationships, and do better in school. But as a developmental psychologist I’ve often wished for resources to help parents deal with worrying in their children. So I was pretty excited when I found a lovely picture book recently at a professional conference: Is a Worry Worrying You? by Ferida Wolff and Harriet May Savitz. This light-hearted problem solving “manual,” based on good emotion science, introduces young children to the idea that worry may be more optional and flexible than they believe—and that they may be able to do something about the suffering it causes them.

As a parent, I’m moved by the realistic examples in the book; as a developmental psychologist, I’m impressed by the sophistication of the advice contained it its slim 16 pages.

The cover illustrates the idea that we are more than our worries, and that worry is something that comes to us like an unwelcome visitor: “It doesn’t ask if it can enter. It just barges in. And it will stay as long as you let it.”

The feeling and qualities of worry are named and described. One of the first steps in managing a feeling is to recognize it—name it to tame it, we say: "A worry is a thought that stops you from having fun, from feeling good, from being happy." "Anyone can have a worry. Parents. Teachers. Brothers. Sisters. Friends." "You can feel tired from a worry. Or sad. Or sick. A worry can feel like a heavy sack is on your back. Only it isn’t there."

Most importantly, the authors offer many strategies for problem-solving. Research shows that young children ages 3-6 tend to ruminate, or spin their wheels, so they, especially, can benefit from help in problem-solving. And older children who worry a lot believe they can’t solve the problem, though their problem-solving skills in other areas are equal to those of children who worry very little.

The solutions in the book are real techniques of cognitive behavior therapy: reframing, reality-testing, self-talk, replacement, distraction, and action plans. The authors season these approaches with children’s imagination, creativity, and humor. A monster under the bed? Sing him, and you, to sleep. A crabby teacher? Think about her feelings and take her a jar of honey. An overwhelming uncle? Offer to play your favorite game so he won’t talk so much. Can’t fix a worry? Think about something else, distract yourself by doing something you enjoy, or imagine that you lock the worry out of the room.

What do children worry about?

Worry exists on a continuum of a human response to a threat, with biologically-based fear responses on the one end and excessive rumination of anxiety disorders on the other. Worry is in the middle, a cognitive system that anticipates future danger.

At the moment of birth, newborns have an instinctive fear of falling that can be seen in the Moro reflex—large grasping gestures in response to a lack of support underneath the body—which is primitive evidence of a burgeoning fear system designed for survival.

At around 8 months, older babies develop a fear of separation—some more than others—once they’ve registered the comfort and security that the adults in their lives regularly offer.

With more brain and cognitive growth, and the related development of imagination and pretend play, 3-6-year olds become afraid of disasters, monsters, imaginary creatures, things under the bed, things outside, unfamiliar noises, and the shapes of shadows. My preschooler was convinced there was a scary clown outside her window watching her intermittently for about a year. Imagination intrudes into sleep, so this is also the time when nightmares can start.

At around age 8, children’s cognitive development allows them to begin to think forward to possible scenarios in the future, and so their worries become more abstract and are influenced by the flavors and conditions of their environment. Studies done in the 1930's, 1977, 1995, 2002, and 2009 on school-aged children show the following trends over time:

1. School and family

School: In the 1930’s, the number-one worry of 5th-6th grade children was “failing a test.” In a 1977 sample, school still ranked among the top three worries, and in 1995, school concerns ranked second—children were especially worried about tests, grades, being called on, and teacher personalities. Recent research shows that when school climates are more child-friendly, children feel better and achievement scores improve.

Family: In the 30’s, children worried about their parents getting sick or working too hard. Beginning in the 70’s, children reported concerns about marital conflict and divorce—about a parent leaving, about with whom they would live, and having to choose between parents.

2. Peer relationships

Children's worries about their peer relationships rank high—they worry about being rejected or excluded by their classmates, and they worry that their close friends will betray them.

3. Social and economic conditions

Children’s worries reflect larger social conditions. In the 30’s (in the middle of the Great Depression), boys worried about economic conditions: how they would find a job, how they would make money, etc. Financial concerns spiked again in 2009 along with the current economic recession. In the 1930s, concerns about personal harm hardly registered, but worries about robbers, bad guys, strangers, kidnappers, threats of violence, and dying, became prominent in the 70’s. And in the 2003 study by Sesame Workshop, children said they worried about bullying and what they saw on television. Health issues showed up in the 1995 study: children said they worried about their own physical symptoms and whether they might need an operation. They also worried about AIDS. Only one study (1995) looked at racial differences and found that black children worried more than white children, but that again will change with shifting demographics and social conditions.

4. Gender differences

Overall, girls seem to worry more than boys.

5. Age differences

Stress is rising in tweens and teens.

How can adults help?

Because of inborn differences in environmental sensitivity, some children are more biologically vulnerable to worrying than others. They produce more cortisol and other stress hormones in response to environmental stimulation. Because of variations in how children respond, adults have to vary their strategies.

Here are some effective ways to help children reduce and cope with worry:

1. Pay attention and listen to children.

Set aside time when children are ready to talk. Both a Sesame Workshop study in 2003 and a large study by the American Psychological Association (APA) in 2009 concluded that parents are alarmingly unaware of children’s worry and that children feel alone with their fears. Fortunately, the APA has published a clearheaded set of guidelines on how to talk to children about worries.

2. Watch for indirect signs that children are wrestling with worry.

Worry themes may show up in preschoolers’ pretend play.

Worry may show up in physiological changes. Children may become more or less restless, sleepless, irritable, or tired, or they may show marked changes in their ability to concentrate.

Worry may disrupt daily routines, interfering with going to school, forming friendships, or completing schoolwork.

3. Take fears and worries seriously and respond sensitively, never belittling or denying the concerns.

When my 3-year old was convinced that there was a ghost in the skylight, we gave her a mantra to say that “helped ghosts move on.” It wasn’t long before she reported that there weren’t any more ghosts there. When my 8-year old was obsessed with the fear of being trapped in her room by a bad guy or a fire, we bought her a chain fire escape ladder that she kept by her window. The fears subsided soon after.

4. Help children problem-solve

Especially younger children who tend to ruminate more than respond constructively.

5. Model good coping

Model good coping with your own stress and get help if you need it. Children are keen observers and take their cues from parents, even from parents’ facial expressions.

6. Shield children from excessive sources of worry

Shield children from scary media, discussion of disasters, economic woes. A famous study of English children who survived the bombing blitz of WWII found that children who went on to develop debilitating stress had parents who did not filter their own fear in their families.

7. Improve school climate

Encourage schools to proactively improve the school climate and adopt an emotion skills curriculum so that more children feel emotionally safe and empowered at school.

8. Enjoy one another.

One of the most protective set of family dynamics happens when children feel that their parents enjoy them. Play, exercise, and blow off steam together. Optimism, gratitude, and pleasure all help to build resilient brain architecture.

9. Seek help

Seek help if children’s worry is excessive--if they spend more time worrying than not, if worry interferes with normal activities, or if the same worry persists for more than a six-month period.

The ability to regulate our feelings matters a lot to our health, relationships, personal well-being, and success. I was well into adulthood before I got on top of my worries, but today's young children have so many more emotion tools available to them. Worry may be part of the human condition, but hopefully parents can help children manage so that their creative energies are less tied up with worry and more freed up to explore their wonderful potential.